Mayan astronomy: the message of the stars and the mystery of life!

Even before commenting on Mayan Astronomy, we need to understand who these people were. The Mayans, Mesoamerican Indians who occupied an almost continuous territory in southern Mexico, Guatemala and northern Belize. At the beginning of the 21st century, more than five million people spoke some 30 Mayan languages, most of which were bilingual in Spanish.

Prior to the Spanish conquest of Mexico and Central America, the Mayans had one of the greatest civilizations in the Western Hemisphere (see Pre-Columbian Civilizations: Oldest Lowland Mayan Civilization).

They practiced agriculture, built great stone buildings and pyramid temples, worked gold and copper, and used a form of hieroglyphic writing that has now been widely deciphered.

The Mayan people

As early as 1500 BC, the Mayans settled in villages and developed an agriculture based on the cultivation of corn, beans and squash.

Around 600 AD manioc (sweet manioc) was also cultivated. They began to build ceremonial centers and, in the year 200, they became cities with temples, pyramids, palaces, football fields and squares.

The ancient Mayans mined large amounts of building stone (usually limestone), which they cut using harder stones such as flint.

They mainly practiced slash-and-burn agriculture, but used advanced irrigation techniques and terraces. They also developed a highly sophisticated hieroglyphic writing system and astronomical and calendar systems. The Mayans made paper from the inner bark of wild fig trees and wrote their hieroglyphics in books made from that paper. These books are called codices.

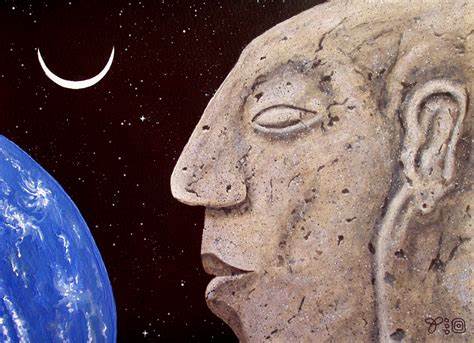

The Mayans also developed an elaborate and beautiful tradition of carving and relief carving. Architectural works, stone inscriptions and reliefs are the main sources of knowledge about the early Maya. Early Mayan culture showed influence from earlier Olmec civilization.

All about Mayan Astronomy

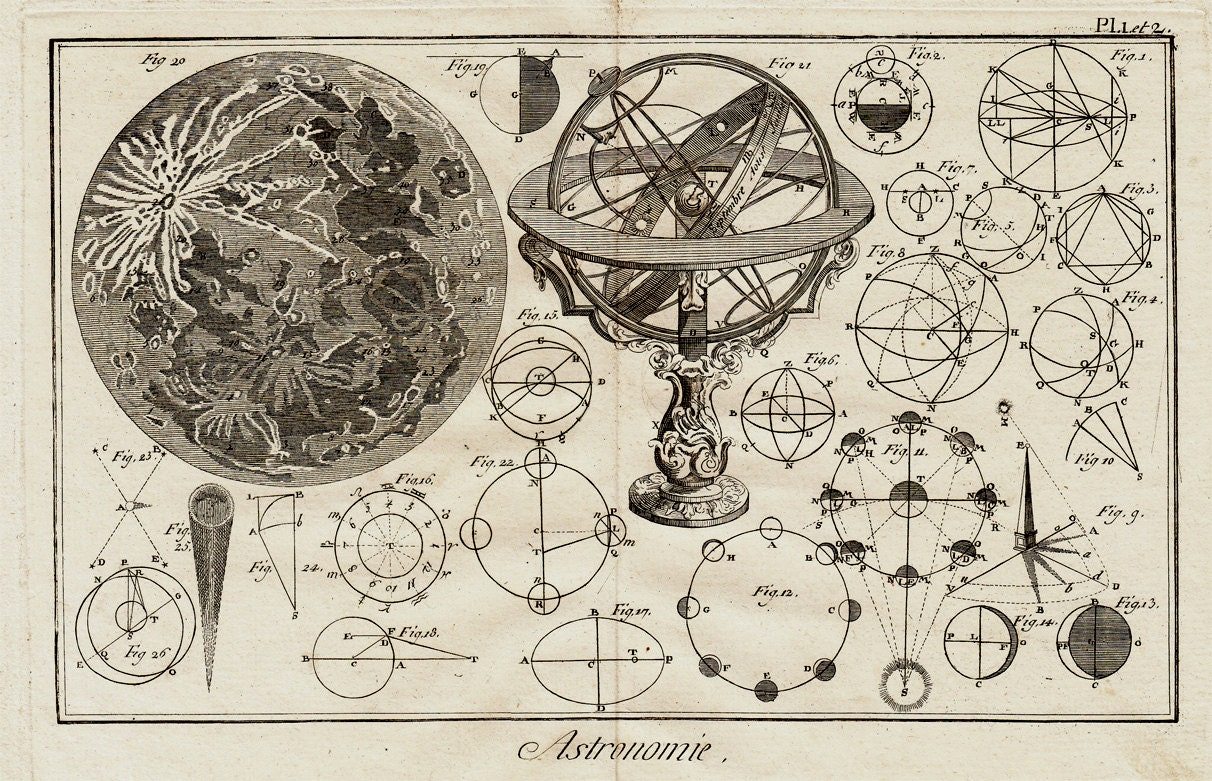

This culture was a keen observer of the heavens and the stars, developing astronomy to such an extent that they were able to develop two major calendars.

Installed in what is now southeastern Mexico and much of Central America, the Mayan peoples built one of the largest and most important empires in the ancient world. Besides the Aztecs, this was the most important culture in the history of pre-Hispanic Mexico.

Its pyramids —especially the one dedicated to Kukulcan— and its hieroglyphic writing system are particularities that especially distinguish this civilization.

However, the Mayans developed an area or discipline that was also an essential part of their daily work and that today continues to be a source of admiration and, above all, of expert study.

This culture was a keen observer of the heavens and the stars, developing astronomy to such an extent that they were able to develop two main calendars: the ceremonial (Tzolk’in), with 260 days, 13 numbers, and 20 day names, and the ceremonial (Tzolk’in) calendar. ambiguous (Haab), 365 days, 18 months of 20 days, with a month of 5 days at the end of the year.

In general, most civilizations in Mesoamerica had astronomy as a fundamental resource to define the periods of their religious festivities and also the precise moment to start the planting and harvesting process, but it was the Mayans who developed this science to a superlative level.

The priests had greater knowledge about the movement of the stars, but the entire population knew that the stars were vital axes to govern a large part of their lives.

The knowledge that Mayan astronomers came to have was more than enough to predict eclipses, follow the movements of planets like Venus or trace an exact trace of the Milky Way – which was considered sacred, they called it Wakah Chan -.

For this civilization, the structure of the cosmos was divided into three main levels with four corners representing the cardinal points.

On the first level was the sky or celestial vault governed by the Bacabs and where the main movements of the stars took place, the most important of which, the sun. So the earth plane was located where men made their common life ruled by the deities.

On the bottom layer was the dreaded Underworld—or Xibalba—a place where the sun went every night to do battle with spectral beings. Once he defeated them, he would return the next day at dawn to rule the Earth.

In the aforementioned hieroglyphic writing, the Mayans left evidence of these stories and of their fondness for the study of the stars. One of the phenomena that most fascinates scholars and enthusiasts of this culture is what happened in the Kukulkan pyramid located in Chichen Itza.

During the equinoxes and solstices of each year, an undulating shadow is drawn over the structure that descends to the serpent’s head that adorns the structure’s foot. This shade gives the appearance of a viper’s body.

What precedes is not causality, it is the result of a construction carried out for this purpose and based on the careful astronomical observation of whoever conceived this temple. Mathematics, religion and architecture combined to offer a phenomenon whose purpose was to simulate the descent of the Feathered Serpent to the full land.

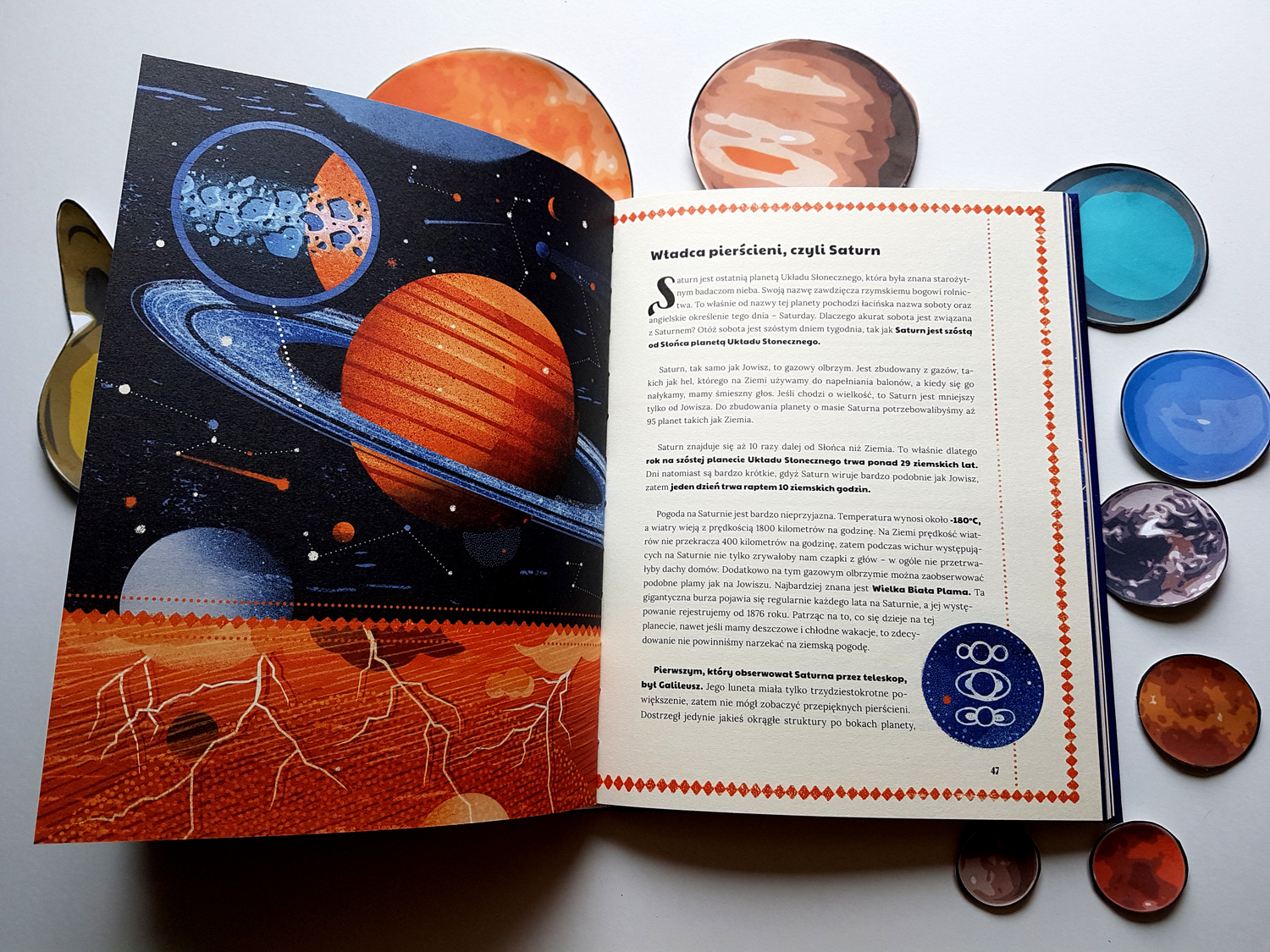

In addition to the sun, the moon was also an important part of the astronomical observations of the Mayan people. Its presence was believed to be of monumental importance in terrestrial life.

The crescent moon was given the attributes of a beautiful young woman, while the waning moon was represented as an old woman who reigned over births. For its part, the Feathered Serpent—that is, Kukulkan—was represented with the planet Venus. They called it Xux Ek, the “Big Star”, and they knew perfectly well that it was the same object that appeared in the sky day and night.

Chichen Itza had an observatory which at the same time served as a temple of worship to Venus. It is surprising how its structure is so similar to modern astronomical centers, which tells us of the great vision and advances that the Mayans had in the study of the stars.

In the Bonampak Temple of Inscriptions hieroglyphics were discovered indicating that the appearance and disappearance of Venus was related to the beginning and end of war missions, which indicates the importance that this celestial body had in the life of the Mayans.

They were able to predict eclipses and make calendars as advanced – even more so – than the current ones. But in the 9th century, suddenly and inexplicably, the Mayans abandoned their most important cities like Tikal and Palenque for good. After all, the great civilization that worshiped the stars could not foresee its rapid downfall and extinction.